VINCE

When I was arrested in December of ’13, my dog Willie wound up living with my friends in the Fillmore County area. He has spent over half of his life there and his dog friends are there, so I know he’s happy, and that soothes me.

The people that are taking care of him I miss just as much. They were not just a part of my life, but they were my life, for years. And although we were all pretty good at drinking, we bonded with each other, and I stayed out of legal trouble for many years. Then, of course, I made a quick decision one night to use meth, and it took only a few months for me to separate from the pack, then leave altogether.

I miss you guys. I think of you daily. Not just you, but your families, who were all good to me.

Seth, our trip to Florida to watch [the Minnesota Twins] baseball spring training games was comparable to me to the best vacations I’ve been on. We had more fun in seven days than most people have in a year. It was “the crippie.”

Curt, you and I have had conversations that have not, and will never again, happen in this world. I cherish every minute we spent together.

Sara. You are a free spirit and a true friend to everybody you encounter. You taught me how to ride a horse. I failed to learn. But that’s because your horses are stupid.

Those three plus me. We were the “Super Best Friends Group” for years. I abandoned them like I abandoned the rest. They belong to the short list of the people I feel worst about. I write to all of them constantly. Some reply, some don’t. But I keep writing.

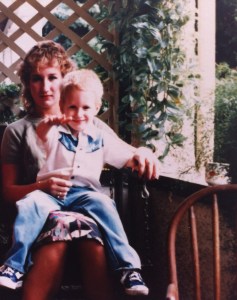

Seth, Vince, and Sara at a baseball game. It was about 101 degrees.

[ANNE: I made an effort to travel with Vince before he left home. I considered it an important part of his education—travel itself, different people and places. We went to Seattle, New York City, and Washington DC, among other destinations. We mostly got along well when we traveled.

When he turned 30 he seemed to be doing so well—as was I—that I offered to take him on a “big trip” somewhere. He had heard me talk about my friends who lived in a stately home (below) in the Scottish highlands, and said he’d be interested in going there. I think he was attracted to the hunting and fishing, the six dogs and two cats, the meat-laden diet, and of course the whiskey. It was a wild, manly, rural place. I thought Vince and my friend Lynn’s husband would get on well together. Maybe Richard would even inspire Vince to aspire to be more.

Before I sunk thousands into a trip, I thought I should make sure he was serious about going, so I told him to get his own passport. I mailed him the form. It would have cost $75. I realize that may seem like a lot when you’re a cook making minimum wage. He said he would do it, then didn’t. So the trip never happened. I was disappointed, but relieved that I hadn’t forced it to happen if he didn’t really want to go.

A few years later he asked me if my offer of a birthday trip was still valid. He wanted to go to watch spring training baseball games in Florida in February with his friend Seth. I said yes. I feel strongly that getting out of your comfort zone is vital to personal growth, and Vince had barely stepped foot out of rural Minnesota in years. Besides, I had enough frequent flyer miles that it didn’t cost me much. So he and Seth went, and apparently had a good time. Don’t ask me what a “crippie” is.]

![IMG_2326[1]](https://breakingfreeblog.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/img_23261.jpg?w=354&h=264)